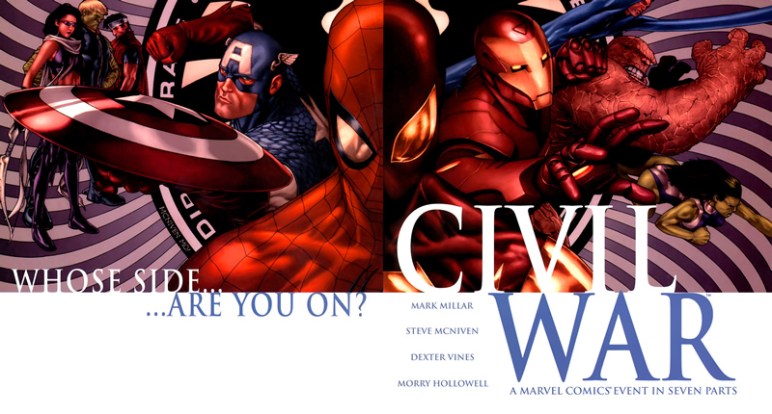

Comics have always reflected the world in which we live. Marvel comics have tackled topics such as politics and global conflict since 1937. For example, characters as early as Namor the Sub-mariner have provided a critical lens on the role of police in protecting civilians from global threats. One explicit example of the influence of outside events on comics is Captain America Comics #1. The cover of the issue, which provides the first appearance of Steve Rogers, features the titular character punching Hitler in the face. This issue acted as propaganda to get kids interested in international politics and push the country into caring about the atrocities in Europe. Captain America remains a politically influential character even to this day. One aspect of his political nature even received attention from mainstream media. The 2006 event, Civil War, features Captain America influencing fellow heroes to fight back against the passing of the Superhero Registration Act (SHRA). Like back in 1941, Steve Rogers’ political ideology was impacted by international tensions post-9/11. The public and governmental fears of future terrorism following September 11th are reflected in the enactment of the SHRA in Marvel’s Civil War.

While 9/11 led to the creation of the USA PATRIOT Act, in Marvel’s main universe, Earth 616, the Stamford Incident led to the SHRA. Civil War #1 opens with a team of teen/young heroes, The New Warriors fighting Nitro. The battle escalates and Speedball gets shot into an elementary school in Stamford CT. The school explodes, killing hundreds of kids. At the funeral of the children, heroes gather and one mother approaches Tony Stark, a.k.a Iron Man. Tony is radicalized by this and vows to prevent anything similar from happening. We soon see Tony advocating for Congress to pass the SHRA. Joe Quesada, the then editor-in-chief of Marvel wrote in a breakdown of Civil War #1 that “what makes Civil War truly unique and like no other big event in the history of comics is that that [sic] there is no real villain. Like sometimes happens in real life, the villain is sometimes the person who has the opposite belief to yours.” This series of events is similar to what happened in real life after September 11th. Following the Al-Qaeda attack, the US quickly passed the Patriot Act, which greatly limited the civil liberties of Americans.

These laws impacted every powered person in the US. However, it is important to note that writers were not consistent in their wording, and therefore different tie-ins can vary in the actual enforcement of the SHRA. The entire SHRA is never explicitly laid out in the pages of the comics. The lack of legal canon so to speak means that each author’s interpretation varied, impacting the outcome of the bill’s enactment. Both the Patriot Act and the SHRA faced public scrutiny and backlash. From the start, Captain America opposed the law, taking a stance on the side of public liberties such as the right to privacy. Iron Man, on the other hand, was one of the first backers of the SHRA, even going so far as to speak to Congress about it. Stark’s advocacy on behalf of the SHRA is to regain the public’s trust in superheroes and to have heroes become government employees with pay and benefits. The conflicting views of Captain America and Iron Man causes the superhero community to divide, which is why the event/series is called “Civil War.” On Iron Man’s pro-registration side, there is War Machine, Vision, Hawkeye, Scarlet Witch, Hulk, and Mr. Fantastic. Against the registration are heroes such as Winter Soldier, Falcon, and Black Widow. Teams like the Young Avengers and Runaways are also amongst the ranks of Steve’s Secret Avengers. While the SHRA divided the hero community, the Patriot Act had divided the country just years earlier. Many were willing to give up their privacy in order to prevent future terrorism, while others saw it as a slippery slope to losing even more rights.

The SHRA and Patriot Act are both directly connected to the removal of rights from both citizens and non-citizens. Like the Patriot Act limiting the right to privacy, the SHRA limited the civil liberties of superheroes because the Act requires them to give up some of their autonomy for the sake of “public safety.” An example of lost autonomy is “the analogous containment of rebel superheroes in an extradimensional prison off U.S. soil where [there are] no lawyers, no courts, no legal recourse.” Similar to the United States’ Guantanamo Bay, Mr. Fantastic built an extradimensional base to hold both villains and heroes who refused to register. Because this base was not on US soil, prisoners were not given the basic rights available to US prisoners such as the right to fair and speedy trial granted by the Sixth Amendment. Scholars could argue that trapping someone in an extradimensional prison could violate the Eighth Amendment’s clause against cruel and unusual punishment. The problem, however, is that the fact that the prison exists in the negative zone means that it is not on US soil (or the soil of any other country on Earth-616). The SHRA was a collaborative effort of both the US government and SHIELD. Therefore one of those groups could be held liable for what groups inside and outside of the government do as a response. While the SHRA was intended to protect US citizens from the fallout of “superhuman activity,” the result was a violation of the Constitutional rights of heroes and villains alike.

A potential way to make the SHRA fit within the confines of the Constitution would be to put it under the War Powers clause which would create another branch of the US armed forces. However, the SHRA doesn’t stand up against draft laws because domestic military intervention is illegal and unconstitutional. Ryan M. Davidson writes that “the depiction of the law involves constitutional, political, and administrative problems, and these problems wind up being what causes a lot of the main plot conflicts instead of what the authors were probably trying to get at, i.e., the social, political, and philosophical motivations for the SHRA as such.” The writer’s worldbuilding leaves big enough holes for scholars to tear apart the feasibility of the SHRA completely. While no one is expecting Marvel editors to include constitutional lawyers, having specific wording laid out in the text or metatext would fill in many of the gaps and allow the political messaging to make sense.

Other than the constitutional issues, another negative aspect of the SHRA’s enactment was the fact that there were villains working for the US government. The team of villains, the Thunderbolts, were overseen by Baron Zemo. While SHIELD was locking up those they deemed criminals for simply refusing to register, they were also letting the actual bad guys back out onto the street with the idea that they would round up members of Cap’s Secret Avengers. Kathleen McClancy writes, “If the SHRA supporters are on their face the bad guys, then either the Secret Avengers must be the good guys, or the good-versus-evil paradigm itself is flawed” She goes on to discuss how Tony Stark is put in charge of SHIELD only to lose his position of power to the infamous bad guy, Norman Osborn. Osborn then has control over Sentry, who McClancy groups in with others as a “super-human of mass destruction.” Therefore siding with the villains to capture heroes goes exactly as the reader expects. The fact that the villains are on the verge of legally killing heroes on behalf of the US government shows that the ends do not in fact justify the means. While the government supposedly had good intentions with Thunderbolts, the fact that it was a spectacular failure should show that the government shouldn’t pick and choose who has rights.

The SHRA also impacted heroes on a personal level. The first character we see influenced by Tony Stark’s fierce advocacy on behalf of the SHRA is Spider-Man. In Civil War #2, Peter Parker reveals both his face and identity to a mass of fellow reporters on the steps of the Capitol Building. While the ramifications of this don’t come into full fruition within Civil War, it does directly lead to death the of Aunt May in 2007’s Amazing Spider-Man #544. Using Erich Fromm’s Escape From Freedom, Travis Langley says that Fromm “extolled the virtues of individuals taking such independent action, of their using reason to establish moral values and evaluate moral dilemmas rather than adhering to values imposed by others. While … obedience can relieve one of the burden of decisions and responsibilities by turning them over to authority figures, taking responsibility for one’s own decisions and actions fosters freedom, independence, and maturity and Spider-Man has long since decided that he cannot stand by without striving to Shape the course of events around him, that having great power meant that he must take great responsibility.” What ultimately sways Parker from the blind faith in Stark to literally fighting for what he actually believes with Cap’s Secret Avengers is seeing the atrocities happening in the Negative Zone Prison, 616’s Guantanamo Bay.

While the existence of the Negative Zone prison is not widely known, there would most likely have been a similar public outcry. In a recent article about Guantanamo Bay, the ACLU stated “Around the world, Guantánamo is a symbol of racial and religious injustice, abuse, and disregard for the rule of law. Our government’s embrace of systematic torture shattered lives, shredded this country’s reputation in the world, and compromised national security. To this day, it has refused to release the full details of the torture program or to provide justice and redress for all the many victims.” Just as the Patriot Act limited rights post-9/11, Guantanamo Bay is an example of how far the US government is willing to go in the name of “protecting citizens.” The SHRA is merely using protection as a facade to violate the rights of both citizens and non-citizens alike with the extradimensional prison.

While the SHRA is a response to an act of violence domestically, the Sokovia Accords as featured in the 2016 film Captain America: Civil War are a response to an international incident. The response was therefore a matter of international politics. The limitation of the rights of powered people is also in question in the MCU. Due to an incident similar to what happened in Stamford, “the United Nations drafted the Sokovia Accords, giving them broad and overarching authority to register powered peoples and see their activities. Despite members’ concerns that the Accords could infringe on basic human rights, they were adopted by the United Nations Security Council.” Under the SHRA, power was given to SHIELD to enact and enforce the new laws, but under the Sokovia Accords, the UN is the one with this power. While Wakanda supported the Accords at first, T’challa withdrew Wakanda from the list of ratifying countries after the UN bombing that killed his father, the former king. Even those within the MCU’s SHIELD questioned how effective the Accords were and whether or not they were ethical. Maria Hill tells Nick Fury that “[t]he Accords might be handy for keeping tabs on enhanced individuals in the field, but regulating them seems a bit of a political pipe dream. Plus, I don’t see Thor signing on a dotted line if he ever shows up again.” Both the Accords and the SHRA were created to form a system of accountability following a terrorist attack, but neither can accomplish that goal without infringing on the rights of those they view as having too much power. The real-world comparison points to this are the invention of the TSA and the No Fly List. The line between keeping a list of names for “public safety” versus persecution is a thin one as evidenced in both the real world and Marvel.

The SHRA demonstrates just how quickly events can cause the erosion of personal liberties. The Stamford Incident acts as the 616 9/11 kicking off the limitation of human rights for powered people. While the Patriot Act allows the FBI to search an individual’s communications without a proper search warrant violating the Fourth Amendment. The government can easily access private information without probable cause. The SHRA similarly denies the right to privacy of American citizens. While the SHRA was eventually dissolved, the US is still seen to be under threat according to legislators and courts who continue the same limitations under a different name. Despite facing intergalactic enemies like Galactus and Thanos, the events depicted in the pages of comic books are and always have been political.

Sources:

- Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, Captain America, vol. 1, Captain America Comics 1, 1941.

- Joe Quesada and Tom Brevoort, “Spotlight Commentary on Civil War #1,” interview by John Rhett Thomas, Print, (2006) 32.

- Ryan M. Davidson, “The Superhuman Registration Act, the Constitution, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” in Marvel Comics’ Civil War and the Age of Terror, 2015.

- Karl E. Martin, “Competing Authorities in the Nation State of Marvel,” in Marvel Comics’ Civil War and the Age of Terror, (2015), 103-4.

- Travis Langley, “Freedom versus Security: The Basic Human Dilemma from 9/11 to Marvel’s Civil War,” in Marvel Comics’ Civil War and the Age of Terror, 2015.

- Kathleen McClancy, “Iron Curtain Man versus Captain American Exceptionalism: World War II and Cold War Nostalgia in the Age of Terror,” in Marvel Comics’ Civil War and the Age of Terror, (2015), 117.

- Travis Langley, “Freedom versus Security: The Basic Human Dilemma from 9/11 to Marvel’s Civil War,” in Marvel Comics’ Civil War and the Age of Terror, (2015), 71.

- Hina Shamsi, “20 Years Later, Guantánamo Remains a Disgraceful Stain on Our Nation. It Needs to End.: ACLU,” American Civil Liberties Union, February 24, 2023, https://www.aclu.org/news/human-rights/20-years-later-guantanamo-remains-a-disgraceful-stain-on-our-nation-it-needs-to-end

- Sokovia Accords,” Marvel Cinematic Universe Wiki, accessed May 11, 2023, https://marvelcinematicuniverse.fandom.com/wiki/Sokovia_Accords

- Will Corona Pilgrim and Andrea Di Vito, Marvel’s Captain Marvel Prelude (New York, NY: Marvel Worldwide, Inc., 2019), 7.